Agile estimation techniques help marketers manage workload

Marketers who estimate can be predictable and confident about how much work they can handle and work at a realistic and sustainable level.

After working with many teams in both software and marketing there’s a fundamental difference I’ve observed – most marketers don’t estimate their work. I’ve also noticed that marketers are more deadline-driven and over-stretched compared to their software counterparts.

While estimating work can feel like an upfront drag, I’ve seen it drastically improve project completion predictability and workload that a team can take on. This is one area where marketers can learn a lot from software teams.

A new way to estimate

While most marketers have abandoned estimating all together because it can be cumbersome, it’s most likely they’re trying to estimate the old way. Traditionally, estimation has been done in terms of measuring days or hours to complete a task. At a project level, T-shirt sizing (S, M, L, XL) is another old-school technique.

Estimating in days or hours works at a very finite level when someone is just about to start work. Before I write this article, I can estimate that it’s going to take me one-to-two hours to complete. That’s a perfectly rational thing to do in the short-term, but it’s a terrible metric for any long-term planning.

T-shirt sizing is a great first pass when a new campaign or project comes to the table. We can have a gut feel if it’s a big or small project, but without any numbers, we can’t use that data to make future planning decisions.

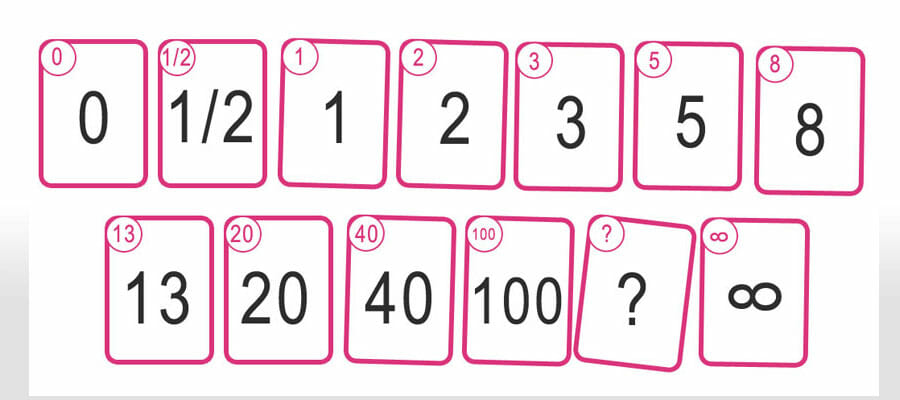

The “agile” way to estimate is by story point using the modified Fibonacci sequence. This sequence of numbers (while a bit geeky in nature) is meant to be an in-precise range that compares one item of work to another.

The estimation is done as a team, rather than for an individual contributor. For example, a blog post may involve a designer, writer, editor and web developer to get completely done and usable to the customer. So the team may estimate that story to be 5 points – it’s not big, but not super small. They may then compare that to a press release and decide it’s smaller and therefore call it 3 points.

Where the number falls on the scale is based on the average team member’s effort (not the expert’s). If the work is really complex, or if it’s something new that the team has never done before, then it’s weighted a little more heavily.

The idea with story point estimation is that everyone on the team discusses the work and comes to a common understanding of its effort. After the team works together awhile, it’s super easy. They may know that they always call a press release a 3 and a blog post a 5.

A few areas of caution: Never compare one team’s estimates to another’s because one team may call a press release a 3 and another may say it’s a 5, even though the effort is the same. The estimation is meant just for the team. Also, never give the story points a conversion to days. If you say 3 points equals 3 days, you’ve completely lost the point of relative estimation – just call it days. The good news is that most marketers are pretty cool with relative estimation and learn it very quickly.

Estimating story points should happen early on in the process as new work items are entered into the team’s backlog (a single, prioritized list for future work). A fun way to estimate this way as a team is by playing Planning Poker online.

Planning team velocity and why it matters

If your agile marketing team is sticky (the same group of people consistently work together) and you’re working in sprints (time-boxed work cycles, typically one or two weeks) you can get a very important data point called velocity.

Velocity is the historical completion rate of work for the team. To earn velocity credit, all work on the story must be complete. So if my blog was written, but not edited, it’s 0 points for the sprint. However, it is all the way done, it’s 5 points.

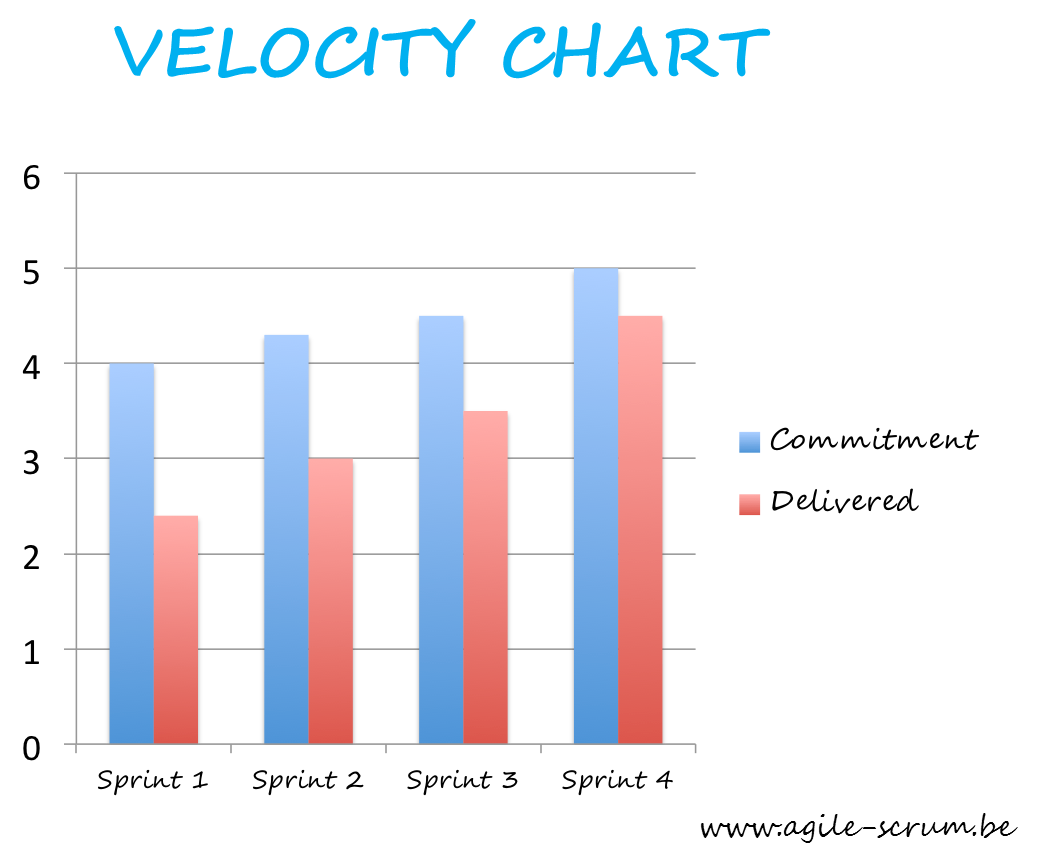

To calculate velocity, the team looks at its completed work in story points over time. In this velocity chart, the team completes between 2 and 4 story points each sprint. This helps for short term planning to give the team an idea of how much work is too much. If they try to put in 10 points of work, it’s unlikely they’ll get the work done. So this shorter-term metric helps a team decide how much work they can realistically commit to based on historical data, not just taking a wild ass guess.

Estimation builds trust with leaders

Every leader I’ve ever met would rather be able to know with certainty that a team is going to get the work done when they say they will. However, most marketers are given false deadlines and agree to them, only to scramble and work overtime to meet these dates, or have to disappoint the leaders when they don’t get met.

Using velocity ranges allow teams to have realistic, upfront conversations early on and to be more predictable with what work they get done.

When a new project comes in, no timeline should be assigned until the team estimates the project. The team may look at the project, compare it to a similar past project and say, “It’s about 20 points.” If the team’s velocity is between 5-to-10 points and they work in one-week sprints, they can confidently say, “It will take us two-to-four weeks, but we’ll give you a better date once we begin.” This gives the team some leeway and gives leadership a high level of confidence that best-case scenario it will be two weeks, worst case a month.

This also gives the team some leverage to break down work into smaller micro-campaigns. They may be able to deliver a subset of the campaign each week, but the total project within a month.

Teams who estimate better manage workload

Marketers are one of the most stressed-out groups of people that I’ve ever worked with (and I’ve worked in marketing too) so estimating and getting predictability can really be a lifesaver! Yes, it takes a little more upfront effort, but marketers who estimate and can be predictable and confident about how much work they can handle can work at a realistic and sustainable level.

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the guest author and not necessarily MarTech. Staff authors are listed here.

Related stories